Courage and Desperation: Federico Rios Escobar’s “Darién”

Arturo Soto examines a book that provides a different political perspective on migration when it is most needed.

How easily someone gets to resettle in another country has nothing to do with individual merit and everything to do with the place they were born. Winners of the birthright lottery can move between nations with minimal risks to their lives and reputations, a privilege that other migrants, frequently prefaced by derogatory words, can only dream of. The reasons why people migrate are varied, but the adversities they face in their country of origin are often ignored by their hosts, except to make their arrival more difficult.

In the period between 2010 and 2020, about 130,000 people, mostly Cubans and Haitians, crossed illegally into Panama through the area known as the Darien Gap. A good way to understand the challenges posed by this mountainous rainforest is that it ended the dream of a continuous Pan-American highway from Alaska (Prudhoe Bay) to Argentina (Tierra del Fuego). The dangers of this untamable territory make it a perfect fit for an illegal industry that feeds on the needs of people looking for a better life. Changes to US immigration policy during the Biden administration had a worldwide effect. In just four years, more than a million people from over ninety different countries — nearly half the number recognized by the United Nations — used this route.

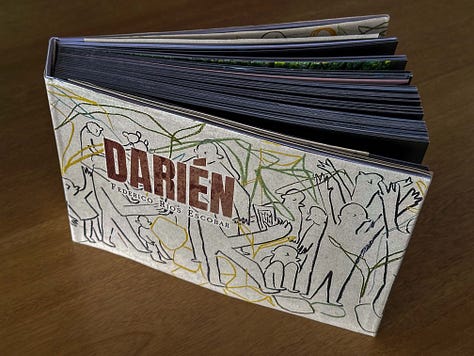

The Colombian photographer Federico Rios Escobar crossed the jungle several times in the company of migrants, risking his life to document the problem fairly. But what does this cliched expression mean when responsibility for the truth dwindles under the influence of artificial intelligence, the parasocial cult of personality, and old-fashioned media distortion? We should consider how our image consumption hinges upon context and circulation, affecting their semantic inflection. While the pictures from Rios’s trips have appeared in prestigious outlets like National Geographic and the New York Times, gathering them in a photobook affords them a different framework. The resulting publication, Darién (Raya, 2024), is a sober yet involving narrative about the dangers and implications of traversing this infamous territory.

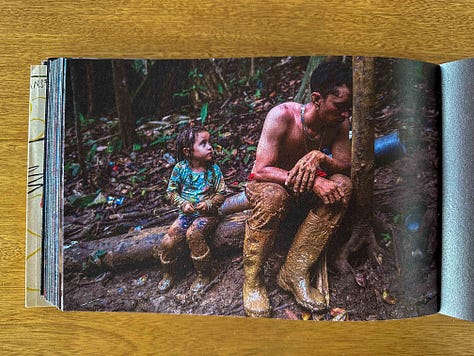

Photojournalism is a frantic genre in which the rush to get (and sell) a story can tempt imagemakers to exaggerate the drama of a situation. However, Rios’s view isn’t defined by the demands of the breaking news format but by his desire to reflect on one of the crucial topics of our age. As such, he settles for a modest range of compositional techniques to avoid letting aesthetics dictate the scope of the pictures. Instead, his work allows us to look closely at the physical and emotional struggles of people acting in precarious conditions. To do this more comprehensively, the book provides extended captions every few pages that describe extravisual aspects, such as biographical details or historical elements that help contextualize this social phenomenon.

Darién begins with Rios’s documentation of Nicolas Maduro’s election in 2013, which detonated the mass migration of Venezuelans into Colombia (an event that reversed the flow of the 80s, when Colombians sought refuge with their neighbors during the narco crisis). The photobook then switches gears to show us what crossing the jungle entails. Rios believes people only venture into the Darien Gap when they are equally desperate and courageous. While there are different routes available, the most common one begins in Necoclí, where guides take the migrants on a boat across the Gulf of Urabá and then through the Colombian part of the jungle. The service costs $170 but grants them protection on the trail and even provides rudimentary health insurance. For instance, Rios tells the story of a girl who accidentally gets a deep cut above her eye and is treated in the middle of the jungle by the medical staff of the group managing the crossing.

Things change drastically once they reach Panama, at which point the migrants become exposed to robbery and extortion, or worse, rape, human trafficking, and death. If they survive, they tread through a long stretch of beach, where the Kuna community offers them basic services for a steep price. Migrants cannot leave this indigenous territory without paying a fee, but the reality is that everyone takes advantage of them every step of the way, with water, food, and WiFi coming at a premium. They only gain access to a shelter when they reach Bajo Chiquito via canoe. The town used to be one of the poorest in the country, but has been transformed by the economic impact of the migratory wave. The trip continues via canoe to Lajas Blancas, where the Panamanian authorities make them board a bus that takes them to the border in twelve hours, a measure that prevents their assembly in the capital and other major cities. Reaching Costa Rica is a triumph, even if they are still very far from the border between Mexico and the United States.

Darién collates work made over almost a decade. Yet, it is sequenced following a spatial logic while lingering on specific people to briefly tell their stories in a way that resembles the editing of Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line. While most of these relate to the jungle, the book includes a small chapter on Afghans stranded in an airport in Brazil, whose only option is to try their luck in the Darien Gap. The publication’s pared-down style is extended to its materiality. It uses uncoated paper and UV inks to give the photographs a muted look that distances them from those in coffee table books that celebrate images for their own sake. Additionally, the hand-drawn cover and map (which shows the routes in more detail) add a warmth that offsets the project’s undeniable bleakness.

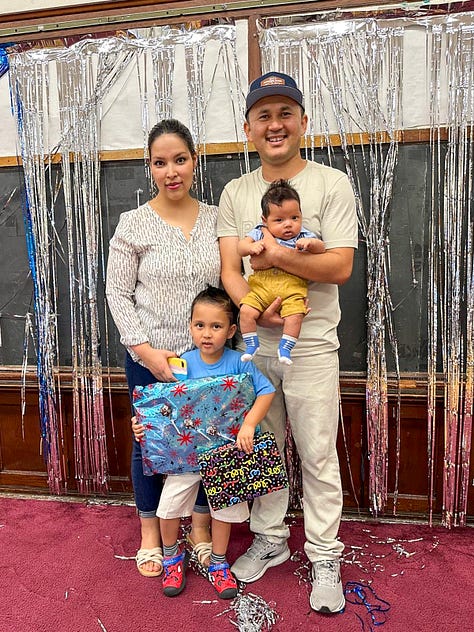

Rios has kept in touch with some of the people he photographed. A section at the end of the book features a few people who managed to reach the United States and have built a life there. The inclusion of these images, made mainly by the subjects themselves for social media, underscores Rios’s humanist ethics. As such, the book’s trim size can be interpreted as a subtle political statement, linking it to Robert Frank’s The Americans. This gesture suggests that these migrants will become the new Americans who will shape the future of a divided country.

What motivates photographers like Rios is the political manifestation of images and their role in defining the history of those who pay for the excesses of the Global North. This particular focus makes Darién a book with the power to change people’s perceptions of illegal migration, perhaps when it matters most.

Arturo Soto is a Mexican photographer, writer, and educator. He has published the photobooks In the Heat (2018) and A Certain Logic of Expectations (2021). Arturo holds a Ph.D. in Fine Art from the University of Oxford, an MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York, and an MA in Art History from University College London. He lives in Wales and is a Lecturer in Photography at Aberystwyth University.

Arturo writes reviews on Latin American photographers for Dispatches: The VII Foundation Blog. Check out his other articles:

The Possibilities of the Actual: Adriana Lestido’s "Metropolis"

Pablo Hare: Sites of Exploitation in Peru

Feeling Out the Past: Graciela Iturbide’s “Heliotropo 37”

A Masked Profession: Federico Estol’s “Shine Heroes”

The Persuasions of Disobedience: Ana María Lagos

Messages of Angst and Hope: “Notas De Voz Desde Tijuana”

The Politics of Window Shopping: Pablo López Luz's “Baja Moda”

Life in a Lawless Town: Juan Orrantia’s “A Machete Pelao”

The Disenchanting Hunt for the Truth: Christo Geoghegan’s “Witch Hunt”

Erasure as a Method of Exposure

The Political Price of Dreams: Pablo Cabado’s "Little Suns on Earth"

The Infinite Resonances of a Single Word: Marisol Mendez’s "Madre"

Walking with Intent: Juan Travnik’s “Materia”

The Poetics of Infrastructure: Thomas Locke Hobbs’ "Rampitas"