No Woman’s Land: Behind the Scenes Documenting Women’s Rights in Afghanistan

Kiana Hayeri and Mélissa Cornet reflect on how they made their award-winning story.

Between January and June 2024, we—Kiana and Mélissa—spent ten weeks interviewing and photographing more than a hundred women and girls across seven provinces of Afghanistan, striving to document their realities with nuance and depth. This project was difficult and, at times, dangerous, but it was also incredibly necessary. Here’s how we did it.

Since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, women have been forced out of schools beyond grade six, barred from universities, most jobs, and even public spaces like parks, gyms, and beauty salons. They are now required to be accompanied by a male chaperone, or mahram, to cover their faces and, under the recent morality law, to remain unheard in public. The country we had come to know in our 20s—a place of struggle but also of dreams—had become unrecognizable.

Shaping Our Approach

Before setting foot in Kabul for this project, we spent hours discussing what we wanted—and did not want—it to be. With a combined 17 years of experience working in Afghanistan, we had witnessed how women were often misrepresented in the media, typically reduced to one of two extremes: the “liberated,” Westernized woman, preferably unveiled or wearing a light hijab or the hidden, voiceless victim cloaked in a burqa.

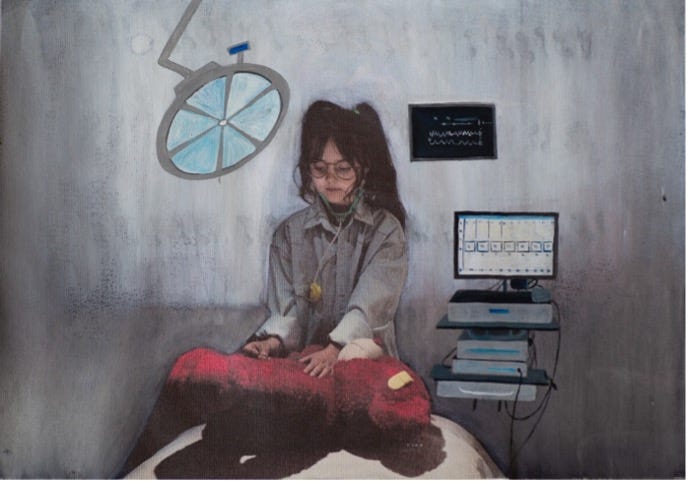

Going beyond these stereotypes meant portraying women in all their complexity while ensuring respect, dignity, and care. While images of women in burqas begging outside bakeries reflect one aspect of Afghanistan’s reality, this was not the only story we wanted to tell. Instead of taking direct portraits of women in burqas, we played with light, shadows, silhouettes, and fabric to protect their anonymity, rejecting the erasure of their identities imposed by that blue fabric. Whenever possible, we showed the women their portraits, ensuring they had a say in how they were seen.

We documented small moments of joy, such as playing in the snow, dancing, putting on makeup, and creating art. In a country that actively denies women their humanity, these moments are acts of resistance.

We also wanted to challenge the conventional visual language of Afghanistan, which often portrays it as a place frozen in time. Inspired by the neon lights that Afghans love to display in the streets, we integrated them into our imagery, bringing color and vibrancy into the homes of women who can no longer freely walk outside.

Our work was deeply collaborative: Mélissa, as a researcher and writer, and Kiana, as a photographer, intertwined our skills, experiences, and creative visions. The interviews and research shaped the photography as much as the photography informed the storytelling. As the project grew, so did our vision, evolving beyond just a collection of images. We developed collaborative art with Afghan teenagers, allowing them to paint their dreams onto their own portraits. We filmed conversations between generations of women, capturing their hopes for the future. We used sketches to depict scenes—like wedding parties—where photography was impossible.

Security and Cybersecurity

Reporting from Afghanistan involved significant risks, as the Taliban have increasingly cracked down on press freedom, detaining and assaulting journalists. According to Reporters Without Borders, the media landscape has been “decimated,” with more than two-thirds of all Afghan journalists–and 80% of female journalists–leaving the profession.

Before entering the country, we established strict security protocols. The safety of the women and girls we met, as well as the people who assisted us, guided every decision we made. Careful assessments preceded each interview: How do we contact this person safely? Who can vouch for us to gain her trust? Where can we meet without drawing attention? How do we travel there? If stopped at a checkpoint, what’s our cover story?

Cybersecurity was just as critical. Mélissa took handwritten notes in a small blue notebook, mixing French, English, and Farsi in a way that was nearly indecipherable. Identifying details—such as names, phone numbers, and addresses—were never written down together. Kiana’s photographs remained uncatalogued until we left the country. These precautions ensured that should our devices be searched, no connections could be traced back to the women we interviewed.

On one particularly stressful day, the sight of a Taliban fighter in our building triggered our emergency protocol: scattering, hiding notes, and deleting recent messages. It turned out to be a false alarm. Another time, while in Bamiyan, we realized we were being followed. The decision was easy: we would not attempt to interview any women that day. Instead, we turned back toward Kabul. Without a security team, we relied on our instincts and those of our local team. Our golden rule was that if anyone, including our driver or interpreter, felt uneasy, we canceled, postponed, or left, no questions asked.

Amidst the tension, small rituals kept our morale up. After a few days of disappointing reporting, playing Nina Simone’s Feeling Good led to our best reporting day yet, and it became our anthem. Moments of joy, laughter, and comfort wove themselves into our weeks of work, especially with the few friends still in Afghanistan.

Trust and Informed Consent

Power dynamics in Afghanistan are stark. A strong culture of hospitality, or ta’aroof, often leads people to say yes out of politeness rather than true willingness. We had to read between the lines, ensuring every interviewee was comfortable participating. We explained the project and its risks in detail, ensuring they could give informed consent. But how do you explain social media to someone who has never used the internet? How do you convey that, once a photo is online, we lose control over it, even if they later change their mind?

As a result, we were conservative in some cases, opting for anonymized portraits even when a woman wanted to show her face. Afghanistan’s situation changes rapidly, and we had to consider the future: what might be safe today could become dangerous in six months or a year. In a society where women’s decision-making power is constantly undermined, we aimed to strike a delicate balance, respecting their agency while ensuring their safety remained our priority.

Building trust requires time. In one instance, we spent several nights in a maternity ward, sharing jokes with midwives until they stopped noticing Kiana’s camera. In another, we immersed ourselves in the lives of Afghan teenagers, attending birthday parties, art classes, and family gatherings.

What is Next?

Much of the suffering Afghan women endure today is driven by the country’s economic and humanitarian crisis—a crisis exacerbated by international policies. The suspension of development aid, the freezing of Afghanistan’s central bank assets, and ongoing sanctions were intended to pressure the Taliban. Instead, they have primarily harmed Afghan women, compounding their oppression.

We never expected this project to immediately change policies. Governments and institutions are already aware of the scale of human rights violations. But we pursued this work nonetheless, documenting these stories for the future, for a time when people will look back and ask: How did we allow this to happen?

It is easy to feel overwhelmed when advocating for a crisis abandoned by the international community. In Dari, there is a saying: qatra qatra darya mesha—drop by drop, a river is formed. So, we focus on what we can do: each platform where we share these stories, each visa secured for a woman to escape, and each donation made to support them. These are small actions that, together, become an unstoppable river.

Kiana and Mélissa presented No Woman’s Land in a VII Foundation online event in January 2025 - you can watch the recording here.

No Woman's Land has since won two awards at the 2025 Pictures of the Year International 82, a 2025 World Press Photo Award, and has been shortlisted for the Amnesty Media Awards 2025.

We want the project to be accessible to all, and thanks to the support provided by the 14th Carmignac Photojournalism Award from the Carmignac Foundation, we have done this by creating a website, No Woman’s Land.

We are now turning the project into a photo book, for which we have a Kickstarter campaign that runs until 24 April 2025. Please consider supporting us!

Kiana Hayeri grew up in Tehran, Iran, and moved to Toronto while she was still a teenager. Faced with the challenges of adapting to a new environment, she took up photography as a way of bridging the gap in language and culture. In 2014, a short month before NATO forces pulled out, Kiana moved to Kabul and stayed on for 8 years. Her work often explores complex topics such as migration, adolescence, identity, and sexuality in conflict-ridden societies.

In 2020, Kiana received the Tim Hetherington Visionary Award for her proposed project to reveal the dangers of dilettante “hit & run” journalism. Later that year, she was named the 6th recipient of the James Foley Award for Conflict Reporting. In 2021, Kiana received the prestigious Robert Capa Gold Medal Award for her photographic series “Where Prison is Kind of a Freedom,” documenting the lives of Afghan women in Herat Prison. In 2022, Kiana was part of The New York Times reporting team that won The Hal Boyle Award for “The Collapse of Afghanistan” and was shortlisted under International Reporting for the Pulitzer Prize. In the same year, she was also named the winner of the Leica Oskar Barnack Award for her portfolio, “Promises Written On the Ice, Left In the Sun,” an intimate look into the lives of Afghans from all walks of life. In 2024, Kiana published a photobook “When Cages Fly”, was selected in the Joop Swart Masterclass and was selected as laureate of the 14th Carmignac Photojournalism Award with Mélissa Cornet.

Kiana Hayeri is a Senior TED fellow, a National Geographic Explorer grantee, and a regular contributor to The New York Times and National Geographic. She is currently based in Sarajevo and tells stories from Afghanistan, the Balkans, and beyond.

Website: www.kianahayeri.com

Instagram: @kianahayeri

Mélissa Cornet is a women’s rights researcher who lived and worked in Afghanistan from January 2018 until after the fall of Kabul. Prior to August 2021, she researched women’s economic empowerment, their involvement in elections, the peace process, and violence against women, among other topics. After the fall in August 2021, Mélissa continued to travel to a dozen provinces for her research, offering a unique perspective from inside the country on the degrading situation of the rights of Afghan women and girls. Since then, she has continued working on women’s rights under the Taliban, publishing papers on the impact of the food crisis on women and girls, on how to include women in aid delivery, on the mental health situation of women aid workers, and on women’s economic empowerment programs in a country where they are no longer allowed to study or move without a chaperon.

She is a cited expert on the issue of women’s rights in the country and has been interviewed by media outlets, including The Guardian, BBC, VOA, The Times, and Frontline, as well as numerous French newspapers. She has appeared on ABC News, MSNBC, France 24, BFM TV, and Arte and has been a guest speaker for events at the House of Commons and at the U.S. Institute of Peace. She was named laureate with Kiana Hayeri on the 14th Carmignac Photojournalism Award in 2024.

Website: www.melissacornet.org

Instagram: @melissacrt

What a fantastic and courageous project - totally inspirational - thank you, your team and the women and girls of Afghanistan for creating this

Unbelievable and so important that the rest of the World is show what exists