Postcolonial Perspectives: Gulshan Khan on the Scars of Apartheid and the Enduring Power of Place

Fiona Wachera

Gulshan Khan’s work is deeply informed by her experiences growing up under apartheid and transcends the traditional boundaries of documentary photography. It weaves together personal narratives, historical memory, and a fervent call for social justice. The South African photographer—a Canon ambassador and National Geographic Explorer–creates stories with a powerful blend of artistic vision and social conscience. My conversation with Khan delves into her perspective, exploring how her personal journey has shaped her visual practice and activism.

Who you are in the world shows up in an image

Born in the twilight years of apartheid, Khan's childhood was indelibly marked by the realities of inequality and segregation. "Even now, if you go back to my hometown," she reflects, "you still see those divisions – the white areas, so-called Colored areas, so-called Indian areas and Black areas." Spatial segregation, a deliberate tool of the apartheid regime, continues to shape the landscape and political dynamics of her KwaZulu-Natal hometown of Ladysmith (which was renamed uMnambithi in 2024).

Khan's experiences with language further illuminate the complexities of belonging and identity in post-apartheid South Africa. Afrikaans, her mother’s first language, was spoken frequently at home, along with English. As the language of the Afrikaner oppressor, this created a complex tension Khan navigated through code-switching to feel accepted. "Like many people, I instinctively learned to code-switch between Afrikaaps [a term signifying the way people of color speak Afrikaans so as to reclaim the historical narrative of the language], the dialect spoken in my community, and the so-called ‘suiwertaal’ or 'pure' Afrikaans as referred to by white people," she explains, highlighting the ways language reinforces power structures amongst marginalized communities.

“I would get special attention from white teachers as if I was some novelty, ‘Ooh maar jy praat so mooi’ they would say and call others to come hear that I could speak ‘their’ language ‘so well’ ‘in a province where Afrikaans was not common at all.[1] My mother protested in the 70’s student uprisings against Afrikaans being the sole medium of teaching in schools, even though it was the only language that she could read and write in at the time. She, like many others, understood how it was being used to oppress everyone. These experiences are not unique to me, in fact they are shared by many South Africans of color.”

This nuanced understanding of language as both a tool of oppression and a source of personal identity informs Khan's approach to visual storytelling, enabling her to capture the subtle nuances of human experience in a society still grappling with the legacy of racial division.

Khan's belief in the power of visual storytelling to transcend language barriers and connect with people on a deeper level is central to her artistic practice. "Who you are in the world shows up in an image," she states, emphasizing the link between personal identity and creative expression. "We cannot separate ourselves from the stories we are telling... We cannot separate climate change from war...We cannot separate politics from anything," Khan insists. She sees photography as a powerful tool for raising awareness about human rights injustices, sustaining dialogue, and inspiring action around critical issues.

Education and activism as seeds of social justice

Khan's early exposure to activism, through her parents' involvement in the anti-apartheid struggle, played a pivotal role in shaping her understanding of injustice and her commitment to fighting for a better community experience. "My parents were very involved in the struggle; they were the foot soldiers doing the work in the trenches," she recalls. “I have early memories of my sister and I carrying in extra plastic stools to the sitting room for meetings held at home by the adults late at night, while all the kids played in the bedroom wondering how come we're so lucky to be together and awake at that hour…There would be printing of pamphlets and marches."

This early immersion in political activism instilled in Khan a deep sense of social responsibility and a belief in the power of collective action and community to challenge oppressive systems. "My mother would have shared something from our home because someone needed it, knowing that we would be able to replace it at some point. I think that sort of awareness has influenced how I move in the world."

Khan's experiences of educational inequality further fueled her passion for social justice. "We didn't have proper resources, textbooks, or enough teachers in government schools meant for Brown and Black kids," she recounts, "and yet we were expected to compete at the same level as students in better-resourced white schools. Of course we were still a bit better off than some other schools in poorer areas, this is what apartheid did." This glaring difference in resources between schools really opened Khan's eyes to the deep-rooted inequities of the education system. It fueled her desire to fight for justice and led her to initially pursue an education in human rights law. Despite taking a different path, that passion for equality still shines through in Khan’s photography and activism today.

Khan’s time in university exposed her to the complexities of navigating relationships and identity in a society still grappling with the legacy of racial segregation. "When I went to campus," she recalls, "that was when I encountered white people at the same level, in a space where we were all supposed to be equals, at least theoretically." This experience challenged Khan's preconceived notions about race relations and broadened her understanding of social dynamics in a South Africa that was being transformed. "There is a massive gap in the education of what was happening only just 30 years ago during apartheid. I don't think there's enough information and education about our slave history either… We didn't learn about our own communities, about our own ancestors, about our heroes," she added. “The way apartheid situated us was divide and conquer. Certain groups were given more privileges than others, which creates deep-seated animosity and tension." Khan's willingness to engage with these complexities, to openly address the challenges and contradictions of race relations, adds a profound dimension to her work as both an artist and an activist.

The myth of objectivity

Khan's work experiences in the photo industry have instilled in her a rich skepticism toward dominant narratives and a critical perspective on the role of the media in shaping public perception. "The myth of objectivity," she asserts, "who is thought to be objective and who is not objective?" Challenging the notion of unbiased reporting, Khan argues that all media, including visual media, is inherently influenced by individual perspectives and institutional agendas.

Calling for more ethical reporting, particularly from Western journalists reporting outside their home countries, Khan sees the parachute journalist as often implicated in violence and injustice. "We have to be more rigorous and introspective within institutions and media houses," she urges, "in how we become complicit in perpetuating violence." She emphasizes the importance of African photographers and Indigenous photo workers worldwide raising their voices and utilizing the platforms they have access to to challenge injustice and advocate for people-centered governance and human rights, even when it involves personal risk or professional consequences. On individual complicity, she reiterates, “When it comes to actually representing or using your voice or using your platform, it's a big responsibility that can come with repercussions, but if not us, then who? And when?”

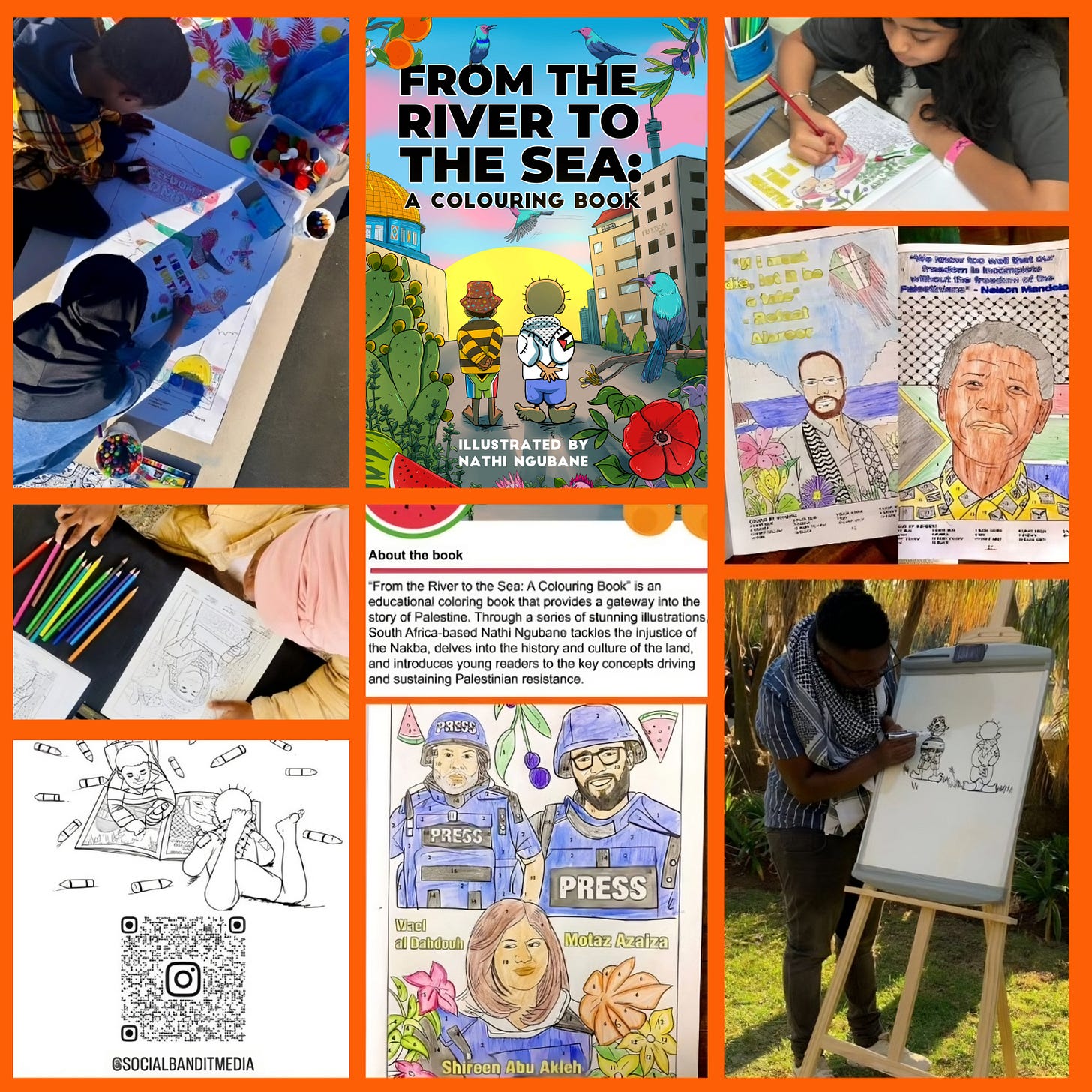

Khan's consultancy and editorial work on "From the River to the Sea," a coloring book illustrated by Soweto-based artist Nathi Ngubane, celebrates the connection between South Africa and Palestine and their shared liberation struggles and exemplifies Khan’s commitment to using visual storytelling for social change. "Initiated by Social Bandit Media this project was made possible mostly through people's donations," Khan explains. "People, friends, got together and contributed their skills as well…[it] was a project born out of love…and born out of...at least for me, a feeling of helplessness, and desperately needing to do something." The project has been a success, selling over 13,000 copies and raising more than US$13,000 for Penny Appeal South Africa to support the Palestinian people.

For Khan, this project demonstrated the potential of collaborative art projects to foster solidarity across borders with tangible impact. "Creating our own tables, even though we may not always have the resources in the beginning," Khan says, reflecting on the spirit that drives her collaborative projects. She finds satisfaction in witnessing the effect of this work: "It is so amazing to serendipitously see kids with the book in public spaces." This experience has further fueled her passion for creating accessible and engaging content for young audiences. "This is something I want to work on a lot more: children's books. We know that visuals can transcend language. Art exists in that liminal space between thought and feeling and is able to transcend all kinds of divisions."

For authorities, however, art can be dangerous. When Israeli police raided the well-known Educational Bookshop in occupied East Jerusalem on February 12, 2025, and arrested the owner Mahmoud Muna and his nephew Ahmed Muna, they confiscated "From the River to the Sea." Along with other publications that highlighted Palestinian resilience and had Palestinian flags on their covers, these books were alleged to be “violating public order” or inciting and supporting “terrorism."

On resisting individualism and embracing collective liberation

Rooted in the values of community, collaboration, and the African philosophy of "Ubuntu," which emphasizes interconnectedness and the belief that "I am because we are,” Khan critiques the Western emphasis on individualism and competition, advocating for a more collective and compassionate approach for achieving social change. "We have to actively remember who we are and understand that there's great value in operating as interdependent communities, which we integrally are." She sees promoting individualism as hindering the collective action necessary to address systemic inequalities and injustices. She believes that by working together in a spirit of abundance rather than scarcity, we can create a more just and equitable world for all.

Khan's critique extends beyond the personal realm to encompass the broader societal context of her work. Challenging the impartiality she sees as prevalent in many organizations, Khan believes this breeds a culture of grayness and discourages open conversations about important issues like politics, race, and inequality, especially within the photojournalism industry. "I am afraid of this kind of neoliberal, capitalistic ideology that I find existing in increasingly corporatized spaces…that breeds this culture where we must all pretend to be the same, where it is politically incorrect to talk about our differences, and where we all need to compete with each other to get ahead.” Khan's photography actively resists this trend, offering alternative narratives that challenge dominant ideologies and celebrate the nuanced diversity and complex interconnectedness of human experience.

Khan shares how photography and visual education can continue to contribute proactively to a broader conversation about social justice and the struggle for equality globally by amplifying the voices and stories of those often overlooked or silenced.

Self-awareness and creative collaboration as community care

"Knowing myself better, knowing my community better, knowing my world better, with deep introspection and also humility," Khan explains, is essential for creating meaningful and impactful work. By understanding her own biases and perspectives, Khan approaches her collaborators, be they adults or children, with greater empathy and respect. She allows their stories to guide the creative process, unlearning the savior complex through dialogue and collaboration. Thus, self-awareness and community are central to her approach to photography and activism.

In November 2024, Khan delivered the prestigious annual Nelson Mandela Lecture at Ghent University in Belgium, offering the audience her insights on social justice and the enduring legacy of academic apartheid in scholastic ecosystems. Following the lecture, Khan's solo photo exhibition at Ghent University, “Strength and Resilience in the Western Cape,” opened its doors. “We are still moving as if we are separate to the natural world when, in fact, we are intrinsically a part of and thus reliant on it. It is a deep arrogance that humankind suffers from.” Khan’s exhibition delves into the interconnectedness of climate change, migration, and healthcare in the Western Cape, South Africa. It is a region grappling with the complex consequences of environmental and social shifts, providing a powerful visual testament to the challenges and resilience of communities as they face complex crises.

Khan's commitment to collaboration extends beyond her immediate community, encompassing a broader network of artists, activists, and organizations working towards social change in multimedia. She recognizes the importance of learning from others, particularly those with different experiences and perspectives. "Leaving room for being led by people that I'm engaging with and collaborating with," she states, "is what in the end shows up in an image and in the writing, and I am constantly learning and hopeful."

Gulshan Khan's journey as a photographer, activist, and multimedia storyteller testifies to the power of introspection and self-awareness in shaping artistic vision and inspiring social change. Her work, informed by growing up in South Africa, challenges dominant narratives, amplifies marginalized voices, and calls for a more just world. Through her powerful images and her unwavering commitment to social justice, Khan’s work reminds us that our individual well-being is inextricably linked to the well-being of our communities and the planet we share. As she eloquently states, "Unless there's collective liberation, we're constantly hurting ourselves. But we should not despair; there are many of us who are kind, and it really starts with something as simple as just being kind."

[1] In our conversation, Khan referred to the forgotten history of Afrikaans. While it developed primarily from 17th-century Dutch spoken by settlers, most people do not realize how Afrikaans was also used in the 19th century by the Muslim Cape Malay population and transcribed locally into Arabic for cultural and religious texts, resulting in what was called “Arabic Afrikaans.” Indeed, the roots of Afrikaans were influenced by various factors, including indigenous African languages, Malay, Portuguese, and other languages, which were spoken by slaves and indentured workers in the Cape Colony. For analyses of this linguistic history, see articles in the Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies journal.

This is the fifth article in Fiona Wachera's series Postcolonial Perspectives, which showcases new photography from Africa and visual stories that foreground embodied experiences and challenge colonial histories.

Wachera is a media strategist and the Storytelling and Content Specialist at The Aga Khan University. Their work blends hands-on design for photo, art direction, and media project management, utilizing varied communication mediums, design disciplines, and research techniques. Wachera has collaborated with storytelling teams at the World Press Photo Foundation, Black Women Photographers, Code For Africa, and the ICRC, amongst others.

Wachera’s previous articles are:

Postcolonial Perspectives: Arlette Bashizi on Documenting Conflict

Postcolonial Perspectives: Jodi Windvogel on Femicide in South Africa

Postcolonial Perspectives: Etinosa Yvonne on Identity and Trauma in Nigeria

The interview/article begins with an intriguing discussion about Afrikaans and code-switching that evokes Everett Percival's recent novel "James" that reprises Mark Twain's classic "Huckleberry FInn" from the perspective of the chattel slave, Jim. Both instances suggest the use of linguistic codes as a transgressive strategy in the struggle against social oppression. This in an important paradigm for the creation international solidarity networks, and Ms. Khan's efforts in this endeavor are commendable. However, while the accompanying images elegantly reflect her personal identity, they do not unfortunately offer any evidence of her ability to do this photographically.

Très intéressant et je prie pour être de la partie un jour.