Sometime in late 1993, I received a call in Sarajevo from Guy Cooper, a photo editor at Newsweek Magazine and, on weekends, a member of a band called the 'Lovehandles'. He had an assignment for me. There was a catch. It was, he said, with a journalist that many photographers found so complicated they didn't want to work with him. Guy, a fellow Brit, had an acute sense of humour. I couldn't tell if he was setting me up, thought I might actually get along with this journalist, or knew I was too poor to refuse. I accepted.

And so began a working relationship that lasted for 15 years and a deep friendship that lasted until the end with legendary foreign correspondent Rod Nordland. The end came last week when his struggle with glioblastoma drew to a close. And what a struggle. He approached this terminal disease like he approached his work, with the kind of relentless commitment to defy the odds I have seen in very few others. Shortly after he was diagnosed in July 2019, he called me and said his doctors advised him that he had a 5% chance of surviving more than five years. "I like those odds". We both cracked up laughing. He beat them, which was never in doubt, and survived until June 22nd, 2025, two weeks short of six years.

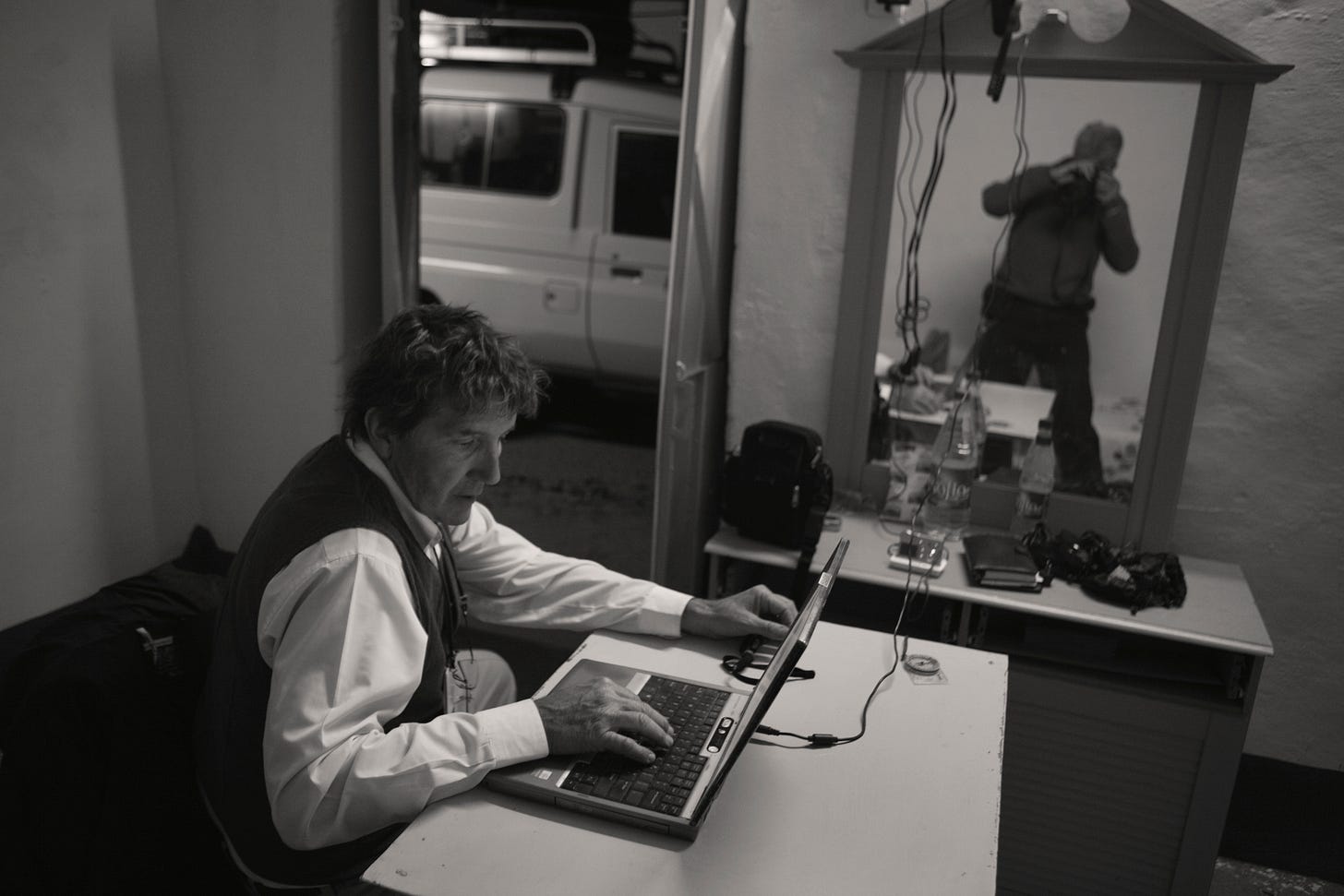

Rod and I would develop stories together; he would pitch them to the foreign desk or chief of correspondents, and I would pitch them to the photo department. Most of our stories were his ideas; he had a nose for them. We spent months and months together every year, making stories in the wars in Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, and many other pretty hardcore places, invariably drawn to injustice. We commandeered a 50-seat bus in Peshawar, Pakistan and drove it to Kabul in Afghanistan to document the end of the Taliban after 9/11; we spent weeks in decaying nuclear power stations in Eastern Europe, escaped from house arrest and went on the run in Darfur, and once spent a week with Michael Schumacher and Eddie Irvine at Ferrari, a rare boondoggle. He was inspiring to work with. His fieldcraft was exceptional. I have been fortunate to work with and be in close proximity to some of the great journalists of the last 40 years. Even in that theatre full of exceptionally resourceful people, he was a master.

His ability to get to a story was legendary. If he approached a one-way street, he would go down it the wrong way and engage in all kinds of subterfuge to get into places where the doors were slammed shut. To say he had an oppositional attitude to authority is an understatement. His passports were full of active visas, constantly renewed. His address book was full of contacts for consuls general and ambassadors whose phones would ring late at night when he needed a visa he didn't have and needed to catch an early flight to somewhere hard to get to. Once he landed, he had a network of stringers like no other. Local men and women with whom he maintained contact and treated well for decades. They were always full of brilliant ideas and great contacts and made significant contributions to the stories we produced.

His toughness and his abrasiveness weren't developed late in life; they came from his childhood, now well documented in his candid memoir, "Waiting for the Monsoon". With a father who was a violent paedophile, Rod spent his childhood trying to survive and learning to be resilient. He would often joke that if he hadn't found journalism, he would have ended up in prison. In a profession where many come from Ivy League schools and well-healed backgrounds, Rod was unusual. He was tough, tenacious, hardcore, and brutally honest. Journalism was his passport out of poverty, a space where he could be the man he chose to be and confront authority. He said what he thought, and if you could take it and give it back, you had a friend for life. He wasn't easy and had high expectations. During the war in Bosnia, he purchased an old Range Rover for the Newsweek bureau. The car came with a laminated typed-out list of instructions, eight pages of them. Check the tyres, change the oil, don't park on a hill, don't smoke - the last instruction was, "Don't swerve for dogs".

During the crisis in Albania in the mid-1990s, Rod established a Newsweek bureau in the capital, Tirana. He took his beloved pimped-out black BMW M5 over from Rome. It was the kind of car every gang leader and trafficker in Albania was driving, and we were pulled over by the police so often that it was hard to work. After one assignment there, I was back home in London, and the phone rang. "Hey Gary, did you leave anything behind you want to tell me about?" I knew this wasn't going to be good, but apart from some rolls of film and shipping envelopes, there was nothing I recall leaving behind; I had a clear conscience. Rod had found a huge stash of weed in a storage locker and assumed it must be a photographer who left it behind. Because his car was such a police magnet, he didn't know how to get rid of kilos of weed discreetly. The last thing Newsweek needed was to be caught with drugs in the house. I had no suggestions but told him not to put it down the toilet because it would block the pipes, and I wished him luck. He chose to flush it anyway, and sure enough, the drains were blocked. A plumber was called, and the neighbourhood descended on the house to watch him fish several kilos of weed out of the drains. The following week, Rod called again. He was a little more agitated this time, "Hey Gary, did you leave anything in the wardrobe in the photographer's bedroom you want to tell me about?" Same answer, nothing I could recall except film and envelopes. I asked him what he had found. "An RPG, a couple of AK 47's and some grenades." Photojournalists push the limits from time to time, but I don't recall seeing any with an armoury before. I am still intrigued and amused that he thought it was possible. This time, he called the landlord because the disposal issue was more complex than the toilet. The landlord was a gangster, and the weapons and drugs were his.

Journalism has lost a true giant, an irreplaceable master of the craft; I have lost a dear friend.

Rod Nordland was a Pulitzer Prize, George Polk, and Overseas Press Club award-winning journalist for the Philadelphia Enquirer, Newsweek Magazine, and The New York Times, which published this story on his life. He was a member of the VII Foundation Advisory Board.

Gary Knight is the Executive Director and co-founder of The VII Foundation.

Sorry for your loss, but you had the ride of a lifetime teaming up with him.