The Image of Construction: Gui Marcondes’ “Ossada”

Arturo Soto examines a book challenging our assumptions about the purpose of documentary photos of architecture.

Ossada explores the recent construction boom in São Paulo through stylish monochromatic pictures that capture the state of flux of a metropolis. However, such large-scale transformations come with the potential fragmentation of the social fabric and the loss of communal histories.

Influenced by his training as an architect, as well as his work in animation and graphic design, Gui Marcondes captures some of the invisible aspects that accompany urban change. Although some of these new constructions expose neoliberalism’s unbridled expansionism, the project can also be taken as Marcondes’ confrontation with nostalgia after spending seventeen years in the United States. The book’s title, which translates as both “bones” and “armature,” alludes to how new buildings don’t just signal renewal, but can trigger an unexpected feeling of melancholy.

The title finds a visual parallel in the building rods and cables on view, one of the many astute counterweights to the rationality involved at the planning stage, which doesn’t manifest the messiness of construction. In an era of machines, prefabrication, and automation, construction sites make painfully clear that the physical strength of the workers is still essential. Yet, Marcondes doesn’t feel the need to belabor this point. Workers are only shown once, on the roof of a building, in an image that also connotes the effort and investment required to produce a sprawl of architectural blandness that now characterizes most modern cities. New constructions aren’t inherently valuable, Marcondes seems to suggest. His critique of the disruptions caused by new buildings is also implied in the vantage point of many of the pictures themselves, which were made from the contentious Minhocão, an elevated highway that has now been partially transformed into a park.

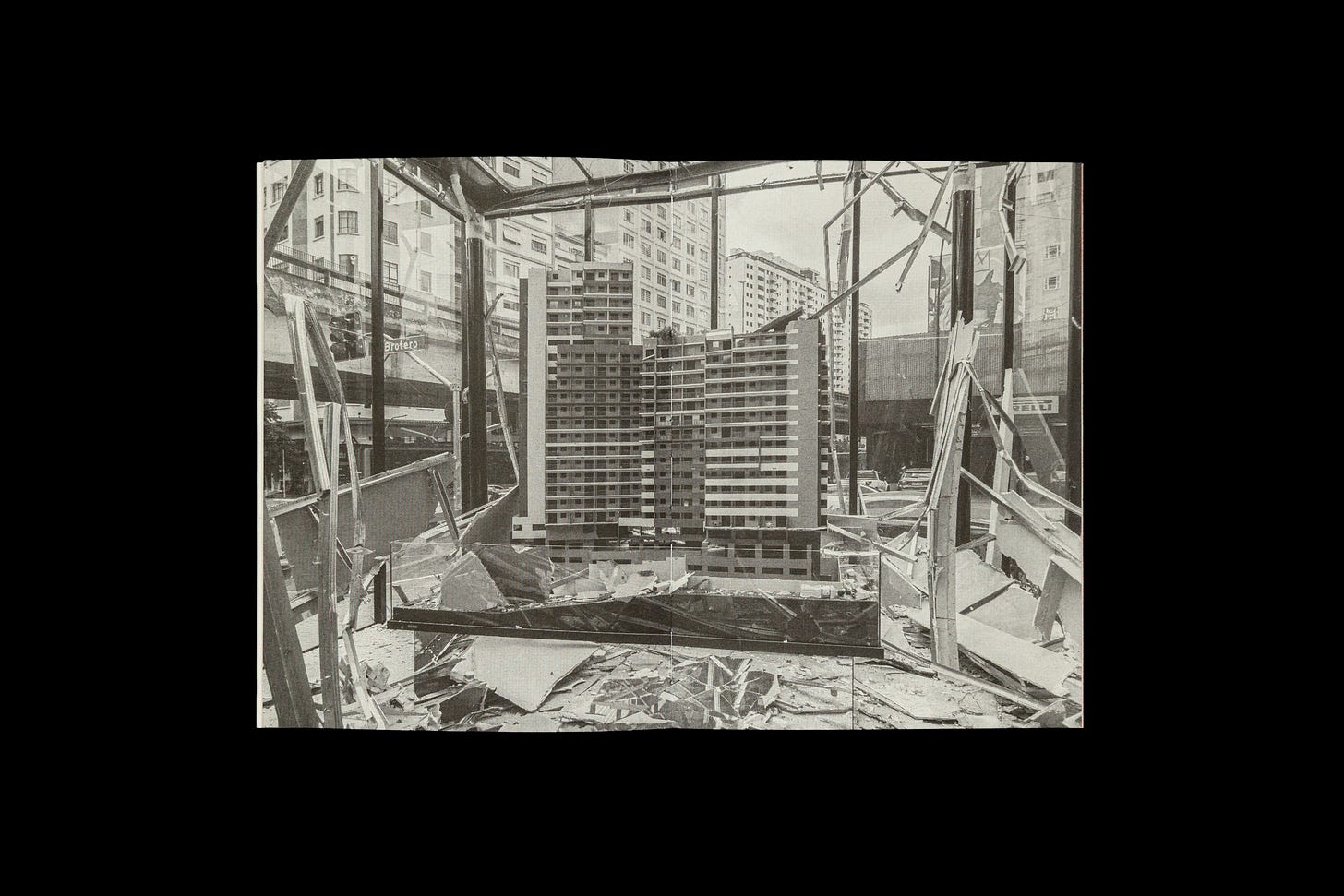

Ossada constantly plays with our perceptions of what the image of a city should be. This is evidenced through photographs of architectural maquettes that challenge the relationship between scale and the spatial politics of a metropolis. In what is perhaps the book’s standout image, one such model stands in the center of a wreckage. The scene is so improbable that it’s tempting to think it was AI-generated, but Marcondes captured it a moment before the showroom that displayed it was dismantled, a reminder that reality can be as surreal as any virtual fiction. This image, along with the many elegant close-ups of construction sites, encourages us to challenge our assumptions about the purpose of documentary photos of architecture.

In another significant picture, a man on a terrace is dwarfed by an immaculate apartment complex. While the photograph doesn’t fool us into thinking the space depicted is real, it does expose something about the alienation created by luxury buildings that segregate public space. An exploitation of the fear of egalitarianism is now common in many parts of the world, and not only via gates and fences. Buildings that were required by law to have affordable units are now using ‘poor doors’ to uphold a social divide.

Printed on a risograph press, Ossada is a materially attractive book. What’s fascinating about this process, a kind of digital screen printing, is that it doesn’t achieve the resolution and smoothness of either traditional or digital offset printing. The resulting texture makes images appear as if they were appropriated from newspapers or other archival sources, rather than being produced with a high-definition digital camera. Nevertheless, this apparent limitation gives them a peculiar character that places them in a productive opposition to promotional materials that present an idealized image of construction. But the charm of this printing process is just one of several elements that constitute the book’s complex discourse.

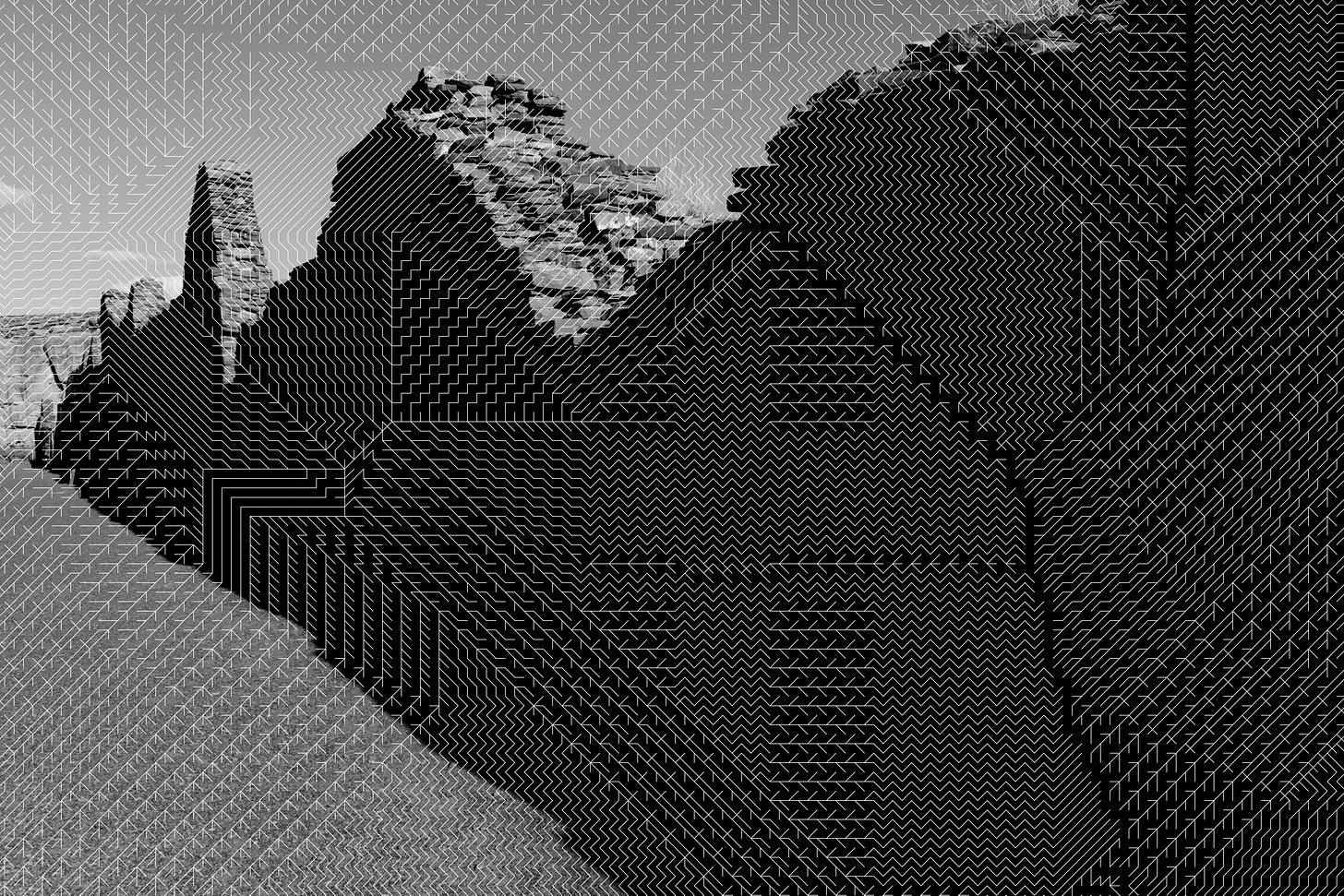

Several pages include digital patterns that hint at the evolution of architectural design and urban planning, perhaps referencing the hyper-rationalization of Brasilia’s master plan and how it differs from the urban chaos of São Paulo. Another element is the gestural drawings, printed in an orange tone reminiscent of traffic cones and high-visibility vests, that remind us of the long journey from sketch to construction that projects go through (though I like to think the drawings are mocking the infamous design process of Frank Gehry). Altogether, these unusual design features intimate the technical operations that shape the urban landscape.

While the book doesn’t directly address specific instances of social segregation or displacement, Ossada can be understood as a subtle political reflection on whether urban growth is driven by need or greed. An image toward the end of the sequence depicts a recently completed high-rise adjacent to a vast, barren plot, raising questions about the infrastructural investment that new developments depend on. Does the building comply with all the regulations, including environmental ones? Will this – and further – housing projects have enough water and basic services? Will the thoroughfares in the area be able to sustain the increased levels of traffic? These considerations are often absent from the aspirational image of the city promoted by developers, and it’s not surprising that their focus on sleek materials and private amenities indefinitely delays the promise of affordable housing. In Marcondes’ book, the continuing fragmentation of the urban landscape feels inevitable, though the way communities around these new structures foster is, hopefully, still a work in progress.

Arturo Soto is a Mexican photographer, writer, and educator. He has published the photobooks In the Heat (2018) and A Certain Logic of Expectations (2021). Arturo holds a Ph.D. in Fine Art from the University of Oxford, an MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York, and an MA in Art History from University College London.

Arturo writes reviews on Latin American photographers for Dispatches: The VII Foundation Magazine. Check out his other articles:

The Possibilities of the Actual: Adriana Lestido’s "Metropolis"

Pablo Hare: Sites of Exploitation in Peru

Feeling Out the Past: Graciela Iturbide’s “Heliotropo 37”

A Masked Profession: Federico Estol’s “Shine Heroes”

The Persuasions of Disobedience: Ana María Lagos

Messages of Angst and Hope: “Notas De Voz Desde Tijuana”

The Politics of Window Shopping: Pablo López Luz's “Baja Moda”

Life in a Lawless Town: Juan Orrantia’s “A Machete Pelao”

The Disenchanting Hunt for the Truth: Christo Geoghegan’s “Witch Hunt”

Erasure as a Method of Exposure

The Political Price of Dreams: Pablo Cabado’s "Little Suns on Earth"

The Infinite Resonances of a Single Word: Marisol Mendez’s "Madre"

Walking with Intent: Juan Travnik’s “Materia”

The Poetics of Infrastructure: Thomas Locke Hobbs’ "Rampitas"